It’s complicated. Is this a preview of government-run health care?

In Atlanta, a not-for-profit hospital with 3,500 employees- filled almost to capacity with COVID-19 patients- had received no COVID vaccine doses as of December 18, and no clear idea of when the first doses might arrive.

Meanwhile, the for-profit Cancer Treatment Centers of America hospital in nearby Newnam reported receiving enough doses to vaccinate its 1,000 staff members, including 148 hospital administrators.

Throughout the state of Georgia, the problem is multiplied. Some hospitals have received doses sufficient to inoculate frontline medical workers and staff members, others have received nothing. Neither greatest size nor greatest need seems to be the deciding criteria for priority vaccine distribution.

The same is true at hospitals in North Dakota, in New York, in California: Tensions over who gets the first doses of vaccine, and who decides who gets the first doses of vaccine, are simmering.

Concern is spreading about how the first limited number of vaccine doses are being administered throughout the nation. Though soon there will certainly be enough doses for everyone, who is getting the first doses now, and why- not to mention who isn’t getting the first doses, and why not- bears scrutiny.

How will the rest of us fare when even some of the country’s 21 million health care workers are left wondering when their turn in line will come? There is also arguably the thorniest question of all, with which the nation has yet to really grapple:

Just who is an essential worker, anyway?

Some hospitals and medical centers are carefully calculating risk in order to vaccinate the most vulnerable staff members first. But there have been plenty of errors, and glaring ones. Hospital administration staff members have been prioritized over frontline medical workers.

In Saint Louis, frontline medical staff members at Barnes Jewish Hospital launched an online petition after older hospital administrators working from home were vaccinated ahead of younger healthcare workers who directly treat infectious patients daily.

“I’m a ICU nurse at BJC,” one woman wrote in the petition, “my coworkers & I take care of the sickest COVID patients with the highest risks for transmission. That administrative staff working from home is prioritized above those on the front line is appalling.”

Some medical staff members fear they won’t be vaccinated until late January.

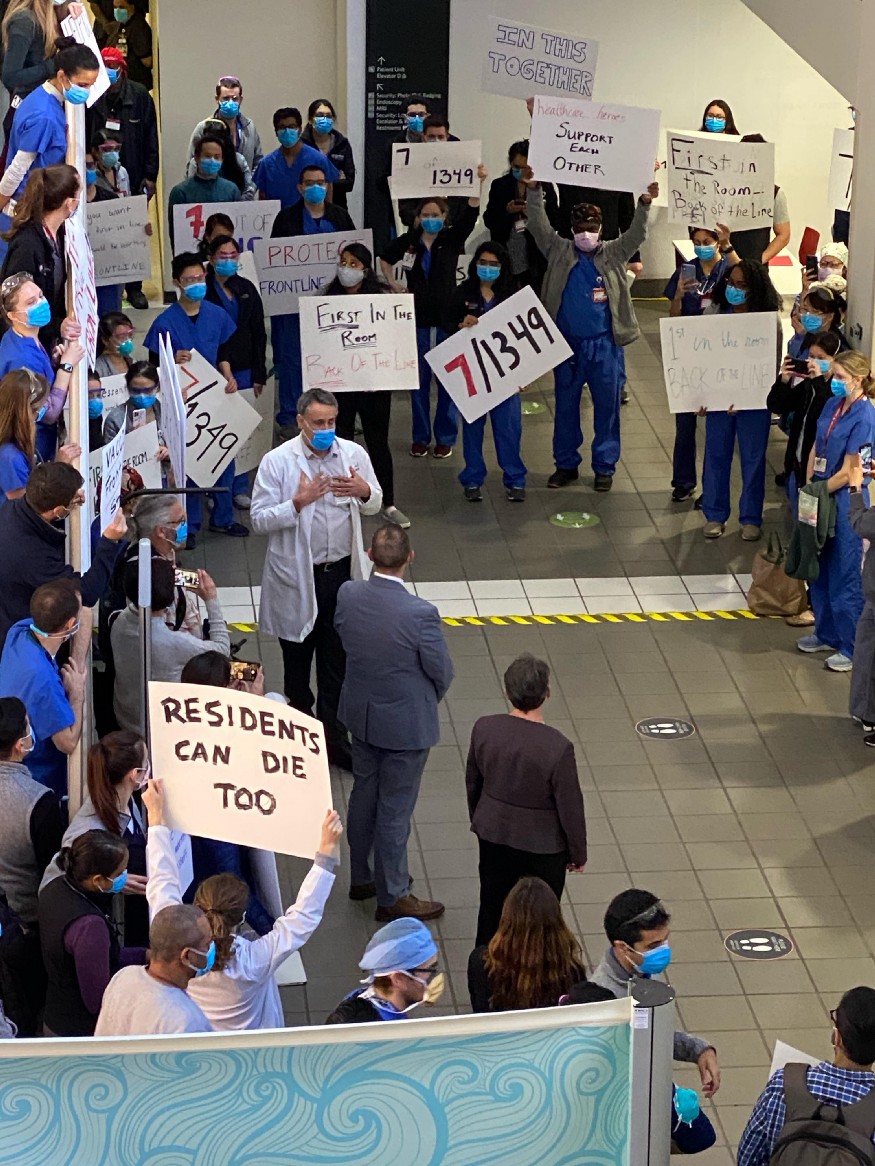

Hospital administrators at Stanford Medical Hospital were scrambling to apologize after over 100 doctors staged a protest over this same issue on Friday. Sanford blamed the problem on an advanced algorithm they used to determine the vaccination schedule.

The “very complex algorithm” somehow missed frontline doctors.

“Our intent was to develop an ethical and equitable process for distribution of the vaccine. We apologize to our entire community, including our residents, fellows, and other frontline care providers, who have performed heroically during our pandemic response,” said Stanford Medicine in a statement.

In Palo Alto, California, a near-identical scene played out.

The same thorny ethical questions are being wrestled with in Florida, where the first doses of the vaccines arrived to great fanfare and some confusion about where, when, and to whom the first doses would be given.

In Alabama, the major scandal is that former Governor Robert Bentley- who resigned in 2017 amid scandal and now works as a doctor at a dermatology clinic- received the vaccine ahead of frontline medical workers.

Some prominent politicians, including outspoken Rep. Tulsi Gabbard, have used this as an opportunity to take a stand, refusing to be vaccinated until frontline medical workers and vulnerable populations receive access.

Gabbard has called upon her healthy colleagues in elected office to do the same. She has also been highly critical of the distribution process, and is perhaps rightfully concerned about the practicality of bureaucrats setting vaccination priority schedules.

However, in Alaska, as everywhere else, the high-stakes game of COVID vaccine line-jumping has already begun in earnest.

The Alaskan court system says its workers must receive priority for the purposes of the “greater access to justice” which in-person legal proceedings would provide.

Alaska’s elected state officials want lawmakers and their staff members prioritized as essential workers. The state’s economic recovery, they argue, depends upon it.

Workers at seafood processing plants, a linchpin of the Alaskan economy, have already been deemed essential. But they want a higher-priority vaccination schedule because the industry employs minority populations who have been hit disproportionately hard by COVID.

Unsurprisingly, the International Foodservice Distributors Association wants its workers vaccinated first. Without healthy truck drivers, they posit, who will deliver food and goods to hospitals and grocery stores?

Following suit around the country, and probably around the world, corporate America is anxious to improve their place in the vaccine priority line. Everyone has a case to make that their workers, their industry, their contribution to the U.S. economy and public safety is the more critical; they aren’t all wrong. There may not be any easy answers.

“I wish I had better words to comfort Alaskans, to say that we’re trying to do this as fairly and equitably as possible. But it’s an impossible task, and I know it won’t feel fair to many.”

“But I can’t do much else about it aside from looking at data and science, and trying to be as transparent as we can,” lamented Alaska’s Chief Medical Officer Dr. Anne Zink, speaking for all of us.

(contributing writer, Brooke Bell)