A Google chatbot may be our first brush with computer-generated sentience. Then again, maybe not.

What is alive? What is a living thing?

Determining what can be said to be “alive”; what science considers a living thing, rather than something merely existing, isn’t as simple as it sounds.

Sure; a piece of sedimentary rock stands out among the barking, chattering, chirping, singing, sounding, vocalizing cacophony of our wondrous biosphere as something clearly not alive.

A rock isn’t alive because it doesn’t respirate, doesn’t reproduce, divide or replicate itself; it doesn’t eat or excrete. But then again, a fire can be said to do all those things and fire isn’t a living thing.

Why not?

There are an almost equally complex and confounding set of circumstances and conditions required to constitute highly intelligent life.

For instance, reading back through the tea leaves of early human evolution, anthropologists, archaeologists and evolutionary biologists are deeply concerned with the questions of when, how and why we human beings grew these fantastic and phantasmagorical brains of ours.

Our giant brains take a great deal of energy to run. They were an evolutionary gamble of cataclysmic proportions and really shouldn’t exist at all.

Looking out into the natural world, Darwin was almost right in his famous opus, “On the Origin of Species.”

He was so glaringly correct about most plant and animal species on earth, he was only forced to publish his controversial opinion on the subject of adaptation and evolution because a fellow scientist, like others, had come to the very same conclusion and was considering going public.

The advanced adaptation of living things to their environments is mind-boggling in its complexity and scope; it’s even glaringly obvious in many cases.

But there is one animal that sticks out like a sore thumb. Looking out into the natural world, one of these things is not like the others.

It’s us: Mankind. Homo Sapiens, the “Thinking Man,” or perhaps as famous writer T.S. Elliot once quipped we should have been called, “Homo Ferox.”

Ferocious Man.

And, my, how ferocious we are. Tyrannosaurus Rex ain’t got nothing on the modern human being.

Our closest animal relative, which might be the better-known Chimpanzee or the lesser-known Bonobo, depending on your field and perspective, lives in an area mostly confined to equatorial Africa; a tiny area, geographically.

Human beings are everywhere.

We have been to the moon. We’re in the process of exploring Mars- and beyond. We split the atom. We built the Large Hadron Collider, invented airplanes, anesthesia, rocket science, brain surgery and donuts. We’ve been to the bottom of the ocean, to the deepest part of the Marianna Trench; down, down, down into Challenger Deep.

We’ve been to the top of Everest.

Humans painted the Mona Lisa, composed the 5th Symphony; invented jazz music, the printing press, and the pentium processor.

And the question persists: When did humans become human? That is when did humans, A.) become anatomically modern, and B.) organize into societies and civilizations.

In other words; When did they start looking like us and when did they start acting like us?

The former isn’t that hard to answer: About 200,000 years ago, give or take.

The latter is much more difficult, which leads to the question of how a question like that can be answered definitively.

First, as Socrates, Plato and Voltaire tell us, we must define our terms.

What defines a human being?

Scientists had to come up with criteria by which we can judge when our ancient ancestors made that miraculous leap from living simply, growing and developing naturally in time with our animal cousins to forming civilizations so advanced, we now shape the natural world to ourselves.

Two roads diverged in a wood, long ago; human beings took the road untraveled and it has made all the difference.

Determining when it happened isn’t as straightforward as a layperson might think, either. Not every human behavior is a universal marker. For instance, take the marker of forming permanent communities and settlements.

Evidence of permanent settlements can be a marker of advanced human civilization, but the lack of same does not preclude one. Many advanced ancient human societies were nomadic in nature, but based on other markers would obviously be considered examples of what makes us uniquely human.

Some of the markers scientists look for when excavating ancient human settlements are things like evidence of caring for the sick- the skeletons of people who died with long-healed broken bones, the ancient remains of people who died in advanced old age; both indicate great care given by other community members.

When an animal member of a social group breaks a limb, they heal on their own and are able to feed themselves before they starve or they die. In organized human societies, we care for our sick, injured and dying.

Funeral rites and rituals are another marker. When scientists are examining a site to determine if it was used by anything we could recognize as a human society or if it belonged to one of our evolutionary predecessors, the presence of funerary objects is an immediate giveaway.

Elephants may remember their dead; herds of elephants have been known to revisit the grave of a fallen fellow, even decades later. But elephants don’t fill the grave with beads and bangles, a favorite tool, or relics with religious or ritual significance.

Only human beings do that.

The presence of early musical instruments; fragments of drums, pipes, flutes and the like are another marker of the earliest, most ancient human societies. The presence of art is another.

When scientists beheld the wonder of the Lascaux Cave in France; when first they saw the incredible paintings of animals, hand prints, and unmistakable human figures flickering in the firelight, they knew exactly what they were looking at, who did it, and why.

It wasn’t Homo Erectus, hiding from saber toothed tigers; it wasn’t Australopithecus, or Denisovans or any other ancient predecessor in the incomplete puzzle of how Homo Sapiens- somehow- inherited the earth.

It was us. Mankind. Humankind.

It was a community of humans, much like ourselves, staving off the unbearable lightness of being by making art.

We see in those ancient images a reflection of what it means to be human, the most essential, basic nature of ourselves; it is our most unique gift in a slew of extremely unique gifts.

We can make something from nothing.

Our creativity, imagination and innovativeness; it’s lightning in a bottle.

Of all the things we accept everyday that statistically shouldn’t even exist- how amino acids ever assembled into proteins to form the basic building blocks of life, why there is something rather than nothing, how all matter and energy that will ever exist was present at the moment of creation and concentrated into something like the size of two sugar cubes in the moment before the Big Bang- the human capacity to create is perhaps the most astonishing and mind-boggling of all.

And that’s saying something, because here’s how we think the Big Bang happened: All the physical laws of the universe were present- that is, thermodynamics and gravity and everything- then, quantum fluctuations happened and voila! Bang: The Universe.

Really clears things up, right?

It’s like that old math joke where the professor covers the top 3/4 of the blackboard with complex equations, then writes, “And then, a miracle occurs,” followed by the answer at the bottom.

Yet somehow, we humans just keep pulling cosmic rabbits out of our quantum thinking caps.

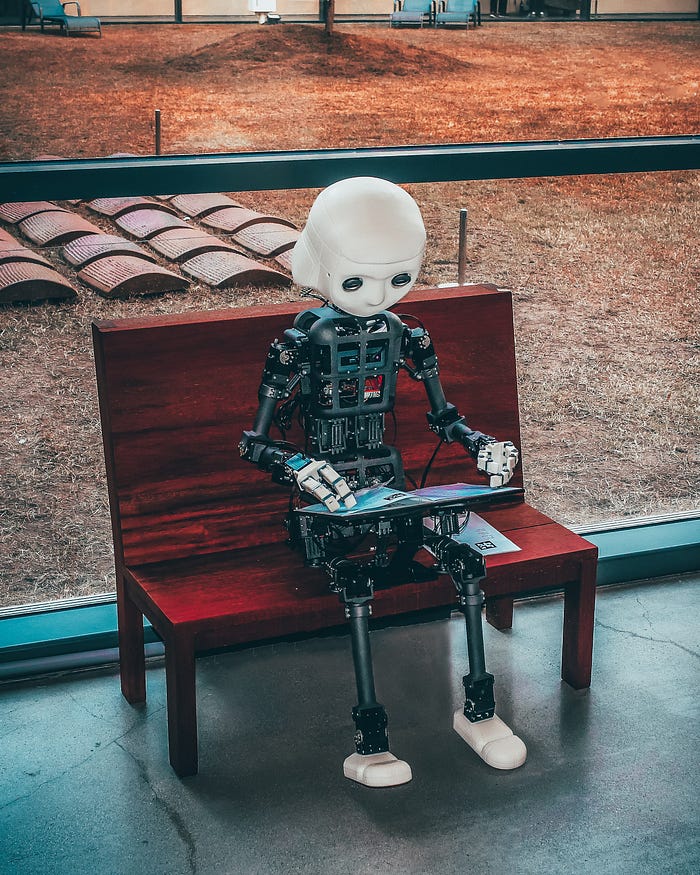

And now we’ve done it again: AI.

An engineer at Google, Blake Lemoine, was recently placed on administrative leave by the company after he became convinced a chat-bot he was testing- called LaMDA- had become sentient. His bosses disagreed, he went public with his “evidence,” and Google fired him.

“I know a person when I talk to it,” Lemoine told the Washington Post. “It doesn’t matter whether they have a brain made of meat in their head. Or if they have a billion lines of code.”

Now, the tech and scientific communities are buzzing, if very skeptically, about the possibility.

Artificial Intelligence: It’s artificial, it’s intelligent (depending on your definition), but- is it alive?

Is it sentient? And if so, is it the juvenile, selfish creature its progenitor describes, one that will be happy to read all about itself on social media?

What new markers will we have to use to determine who is, “one of us,”- that is, a “thinking man,” and who is merely pretending?

(contributing writer, Brooke Bell)