“This will probably be the largest increase in educational inequity in a generation,” concluded a recent Harvard study of 2.1 million students.

“Using testing data from 2.1 million students in 10,000 schools in 49 states (plus D.C.), we investigate the role of remote and hybrid instruction in widening gaps in achievement by race and school poverty,” began a recently-released Harvard study, “The Consequences of Remote and Hybrid Instruction During the Pandemic.”

“We find that remote instruction was a primary driver of widening achievement gaps,” the study’s authors, Dan Goldhaber, Thomas J. Kane, Andrew McEachin, Emily Morton, Tyler Patterson, and Douglas O. Staiger, concluded ominously.

It was only the opening paragraph.

America’s report card on public school pandemic responses didn’t get much better from there. In fact, it got a whole lot worse.

Learning losses were as bad as opponents to prolonged school closures warned they would be, and worse than supporters of extended closures could ever have imagined.

“Math gaps did not widen in areas that remained in-person (although there was some widening in reading gaps in those areas),” the study continued. “We estimate that high-poverty districts that went remote in 2020–21 will need to spend nearly all their federal aid on academic recovery to help students recover from pandemic-related achievement losses.”

After establishing how the authors were able to, “distinguish pandemic-related achievement losses from pre-existing differences in achievement growth by student and school characteristics,” the extremely well-researched study broke the terrible news.

“We find that the shift in instructional mode was a primary driver of widening achievement gaps by race/ethnicity and by school poverty status,” the authors concluded. “Within school districts that were remote for most of 2020–21, high-poverty schools experienced 50 percent more achievement loss than low-poverty schools.”

“In contrast, math achievement gaps did not widen in areas that remained in-person (although there was some widening in reading gaps in those areas),” the study continued, including findings like, “High-poverty schools were more likely to go remote and they suffered larger declines when they did so,” and, “the widening racial gap happened because of negative shocks to schools attended by disadvantaged students.”

The report card on remote learning was dismal.

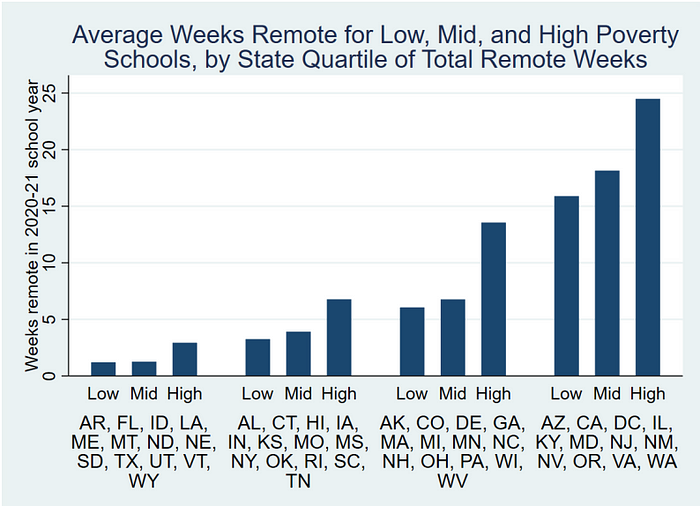

“We observed large differences in remote instruction by state,” the study’s authors wrote, directing readers to a diagram showing states, “sorted into four categories based on percentage of students in remote instruction.”

“High poverty schools were more likely to be remote in all four groups of states, but the gaps were largest in those states with higher rates of remote instruction overall,” the study went on. “For example, in high remote instruction states (including populous states such as California, Illinois, New Jersey, Virginia, Washington and the District of Columbia), high-poverty schools spent an additional 9 weeks in remote instruction (more than 2 months) than low-poverty schools.”

“In states with the lowest rates of remote instruction (including populous states such as Florida and Texas), high poverty schools were again more likely to be remote, but the differences were small: 3 weeks remote in high poverty schools versus 1 week remote in low poverty schools,” the study found.

“The main effects of hybrid and remote instruction are negative, implying that even at low-poverty (high income) schools, students fell behind growth expectations when their schools went remote or hybrid,” was the unassailable conclusion.

Bottom line: When schools went remote or hybrid, students lost.

“High poverty schools were more likely to go remote and the consequences for student achievement were more negative when they did so,” the study’s authors found.

“Throughout the country, local leaders made difficult choices about whether to hold classes in-person or remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the authors allowed in their conclusion.

“There were valid reasons for differing judgements- including differing risks related to local demographics or population density as well as real uncertainty about the public health consequences of in-person schooling,” the report continued, delicately. “While we have nothing to add regarding the public health benefits, its seems that the shift to remote or hybrid instruction during 2020–21 had profound consequences for student achievement.”

“In districts that went remote, achievement growth was lower for all subgroups, but especially for students attending high-poverty schools,” the authors wrote in conclusion. “In areas that remained in person, there were still modest losses in achievement, but there was no widening of gaps between high and low-poverty schools in math (and less widening in reading).”

Can it be fixed?

Depressingly, the study’s authors concluded that, “in high poverty schools that remained remote, leaders could provide high-dosage tutoring to every student [and] still not make up for the loss.”

“Depending on whether they remained remote during 2020–21, some school agencies have much more work to do now than others,” seems rather an understatement in light of that fact.

“If the achievement losses become permanent, there will be major implications for future earnings, racial equity, and income inequality, especially in states where remote instruction was common,” the study’s authors ultimately warned, though this is hardly the final chapter on 2020–21 school closures.

Reports like this are only the first, leading to even more thorny questions about extended public school closures and the long-term negative impact they had on student outcomes. This study’s sample size, though it consisted of 2.1 million students and 9,692 schools, only covered grades 3 to 8.

What about high school students attending public schools which stayed closed to in-person learning throughout the majority of 2020 and 2021?

On this subject, more than any learning losses, America’s report card on public school pandemic responses may be even worse than an “F”. There are early indicators that a great many at-risk high school students already in danger of dropping out left school in spring of 2020 and never went back.

There are other considerations in this age demographic as well.

The mental health of America’s pre-teens and teenagers has been adversely impacted by school closures: Of this there can be little doubt. Elevated suicide attempt rates, a worsening addiction crisis, plus growing rates of depression and anxiety all seem to be bitter fruits of the pandemic and the U.S. pandemic response.

While the Harvard study’s authors were reluctant to wade into the debate as to whether or not all these closures were necessary to preserve public health, the New York Times hasn’t been as reticent.

“Remote learning was a failure,” concluded David Leonhardt for the New York Times on May 5, 2022, citing this study among others and labeling prolonged public school closures, “what economists call a regressive policy, widening inequality by doing the most harm to groups that were already vulnerable.”

“Were many of these problems avoidable?” asked Leonhardt. “The evidence suggests that they were.”

“Extended school closures appear to have done much more harm than good, and many school administrators probably could have recognized as much by the fall of 2020,” Leonhardt went on. “In places where schools reopened that summer and fall, the spread of Covid was not noticeably worse than in places where schools remained closed.”

“Hundreds of other districts, especially in liberal communities, instead kept schools closed for a year or more,” Leonhardt concluded. “Officials said they were doing so to protect children and especially the most vulnerable children. The effect, however, was often quite the opposite.”

(contributing writer, Brooke Bell)